As it turns out, I rest for too long. I eat, shower and then sleep for an hour. But as I wake, I look to at the trackers to see Shawn is closing in on the checkpoint. My precious gap is fast disappearing.

I leap from my bed and race to my bike, keen to not give him the psychological advantage of seeing me. I pass him on the road out of town, but he does not look well. He is sitting rigidly upright and doesn’t spot me (I later learn that he has hurt his neck and is really struggling). Despite this, I know he is an incredibly tough competitor and, with Niel close behind, I decide to put as much distance between me and the checkpoint as possible. With only 177 kilometres to the finish, I know that even a gap of 20 kilometres should be more than enough.

I push hard for 90 minutes, with my legs feeling rejuvenated by sleep and adrenalin. Despite almost 600 metres of climbing in the next 40 kilometres, I somehow average over 25kmph. With only 60 minutes’ sleep in the last 36 hours, I’m surprised how good I still feel.

Then, I hit a 70-kilometre section of gravel that begins with a fast, rutted descent, taking me down into a broad valley that is filled with villages. As the track levels out, the light begins to fade and lightning flashes over the valley ahead.

My phone then buzzes with the news that Niel is apparently hot on my tail. He has clearly only stopped very briefly at Checkpoint 4 and is now back to chasing me.

This knowledge, combined with the storm ahead, concerns me. Whilst I’m feeling strong, I know that Niel’s setup is much better suited to wet gravel than mine. He is running fatter, grippier tyres and has mountain bike cleats. My slick 35mm tyres and road cleats may have given the edge on the tarmac, but will I rue the gamble now?

I push hard to make the most of the remaining light and the dry conditions. But soon torrential rain is splashing on the gravel around me and the last remnants of daylight have faded. I continue steadily along, coping with the worsening conditions, until suddenly my wheels hit thick mud and come to an abrupt halt.

This clay-like mud has coated both wheels and even been sucked up onto my drivetrain, making it impossible to pedal. A couple of locals helpfully point torches at my bike as I claw mud off the frame and cranks with my bare hands. I press urgently on, following a local cyclist for a bit as he picks a safe route between mud traps.

However, my tyres slither on the slippery surface and, eventually, on a particularly churned up section, I keel over and land in the mud, unable to unclip my feet. Frustrated, I walk my bike for a while, ever aware that Niel must be closing in on me.

I know that I have a cushion and just by keeping moving, I am delaying what I now consider the inevitable. If I have to, I will walk and carry my bike through the remaining 50 kilometres of mud. I am not about to let this storm undo the hard work of cycling 500 kilometres without sleep. Despite the fatigue I must be battling, I feel energised and focused. I press stubbornly onwards.

Unfortunately, even walking the bike becomes impossible when I hit the next slope. This resembles a ploughed field, and the mud has soon again clogged my wheels and cranks. Refusing to give up, I hoist my bike onto my shoulder and press on in pitch blackness, struggling to walk in my road shoes and with no light from my dynamo.

At the top of the hill, I claw mud off my bike with my fingers again and continue. The next hour or so is spent walking, cycling or carrying my bike. I begin to get a knack for picking the best route and often stick to cycling through puddles, where I know the water will prevent the mud from forming clogs and wash my wheels clean.

Eventually, I cross a long bridge over a marshy riverbed and, although I’m held up at an army checkpoint for a few minutes, the track improves enough that I am now able to cycle for long stretches at a time.

To my astonishment, Niel still hasn’t caught me and the gap appears to be holding firm. With this, my racing mind slows down a little and processes what I’ve just experienced. I realise that, of course, his fatter, grippier tyres would be little help in these awful conditions. The severity of the weather has effectively levelled the playing field, totally nullifying his advantage and forcing us both to dismount.

As this reality sinks in, I’m relieved, but I press on anyway. The next two hours are spent in a state of total concentration, constantly picking the best line through the mud and edging ever closer to the final 66 kilometres of tarmac. It is painfully slow, but I do not stop.

Right before the tarmac begins, the track has been torn up and I hit the stickiest mud of the entire ride. I drag my bike for half a kilometre, before eventually reaching the tarmac. Here, a sense of total relief engulfs me. I know that – bar a mechanical – nothing is now going to stop reaching the finish line in second place.

Scraping mud from my chain and wheels, I begin the slow spin back to Kigali. The gravel has taken its toll on both me and the bike. My front brake is useless and the zips have failed – clogged with grit – on two of my bags. Mentally, I have been totally fixated on the end of the gravel for hours and this tarmac stretch goes incredibly slowly, despite a creeping sense of euphoria.

On the edge of Kigali, company arrives in the form of the film crew who have been documenting the race. Last time Ryan and Leandro saw me, it was around midday on day one and I looked like I might puke. Now, it’s two and a half days later, and I’m about roll over the finishing line in second place. As I chat away to them, we’re all grinning – revelling in the change of fortunes.

I finally arrive back at the Onomo Hotel at 03:40 on Wednesday morning, 71 hours after I left. Simon and a gaggle of hardy volunteers are there to greet me. I climb off my bike and the race is over. I’m a long way behind Ultan in first place, but I don’t care. It has been an epic ride right from the start, culminating in a 12-hour slog through storms and mud.

A few hours later, after a brief sleep, I go down to breakfast to see a filthy-looking Niel sitting there, still in his lycra. He is grinning, holding a beer and close to delirious with sleep deprivation. We immediately congratulate each other and there is an odd sense of camaraderie. Although we never saw each other during the previous night, it feels like we shared the experience – each of us battling the mud rather than one another.

And it is this, I realise, that makes these races so special. As everyone rolls over the line during the following days, they all have stories from the race – their own tales of adversity and adventure. Ultan may have been the worthy victor, but there are countless personal victories littering the field behind him.

*Photos kindly supplied by Race Around Rwanda. Credit goes to all the photographers but especially to Ryan Le Garrec and LeanDro Deldime for their hard work following the race during all hours and conditions*

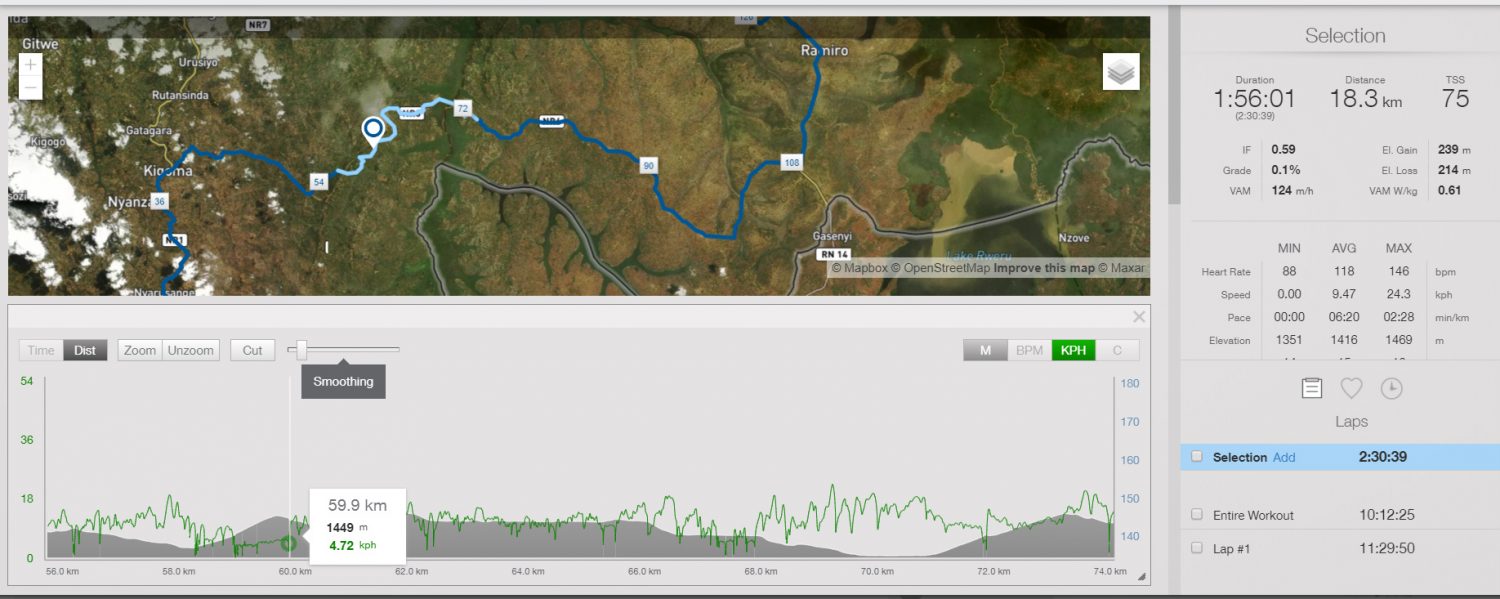

Ride 3 Stats:

177km – 2,142m climbed – 17.5 kmph average – 10:12 moving and 11:29 elapsed

Strava here

Race Stats:

962km – 15,193m climbed – 19.1kmph average – 50:30 moving and 71:08 elapsed